The exhibition’s title, Like water by water, is adapted from the writings of self-taught geologist John Hardcastle (1847-1927). Hardcastle was born in England and, as a child, settled in Timaru in the 1850s, soon growing fascinated by its geography. He spent decades studying the geology of the region and described it as a landscape formed of and by water: through the actions of rivers, glaciers and oceans, all spanning tens of thousands of years. These successive actions left visible geological traces of ancient climates that he was among the first in the world to recognise. Hardcastle’s research is now known as palaeoclimatology and it has become a key field of research in the context of today’s alarming environmental crisis.

Similarly, Like water by water imagines the landscape as holding a number of overlapping and cyclical histories. Each artist in the exhibition draws from elements of the physical environment: limestone, fossils, pigments and clay. These materials are imbued with speculative, relational, ecological and cultural narratives. Entering the gallery, visitors encounter a series of craggy sculptures on plinths by Suji Park. These works fuse together seemingly incompatible materials used in art and industrial applications: paper and epoxy clay, plastic and LED lighting, as well as shards of broken and recycled ceramics. They are reminiscent of archeological relics or primordial creatures and gesture towards the plastic-bonded rocks of emergent and future geology.

Recalling her early experiences as a migrant to Aotearoa, Park notes how making became a way of communicating: improvising and composing within the gaps afforded by language. By piecing together materials with multiple temporal and geographic timelines, Park’s sculptures interrogate the intersection of memory, history, and place. The sensory experience of language is also captured in her titles. Beatdol is a portmanteau meaning ‘light’ and ‘rock’ in Korean, and her Feverhead works (Oaah, Oori and Oyo) play with the letter ‘O’ as direct reference to the mouth and speech. Phase I encases a holographic textile in resin, fossilising it. In 2015, Park moved back to South Korea, taking many fragments of ceramic with her, which the artist continues to use in her new works. In Park’s work, processes of accumulation and fracture form a continuum, reflecting the artist’s itinerant experiences.

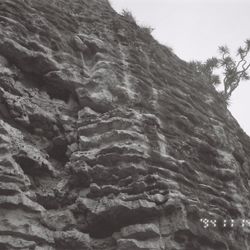

Fiona Pardington’s photograph Pouakai (2006) from the Aigantighe collection stems from her ongoing project to document remnants of the pouākai Haast’s eagle. The pouākai was the largest and heaviest eagle ever known, with a three-metre wingspan and talons as big as a tiger’s claws. It lived in the foothills and plains of Te Waipounamu before becoming extinct 500 to 600 years ago. Initially, European settlers in Aotearoa believed that the enormous eagles of southern Māori oral traditions were mythological creatures, until bones of the pouākai were first uncovered from farmland swamps in the early 1870s. The rock drawing depicted in Pardington’s photograph was only recently rediscovered, as it is difficult to access, being drawn on the ceiling of a narrow cave high up a limestone cliff face. Pardington has a longstanding affinity with the pouākai along with other extinct native birds such as the huia and whēkau laughing owl. This has led her to seek out rock drawings of pouākai, pouākai fossils and artefacts made from their bones now held in museums, and a range of texts on historic and prehistoric sites associated with where the pouākai lived. These are deeply felt encounters for Pardington. She is fascinated with what it must have been like for southern Māori to live amongst pouākai before they disappeared as a living species.

Pouakai is printed using the Fresson process, a unique 19th century technique that stems from early charcoal printing. Successive layers of coloured pigments are affixed to paper over long exposures, gradually rendering a grainy, matte surface for the print. This printing process is sympathetic to the deliberate nature of rock art whereby finely ground pigments, bound with weka or shark liver oil, are applied to a porous rock face, sometimes reapplied or redrawn over several years. Each of these techniques then embodies a durational experience of time in its image.

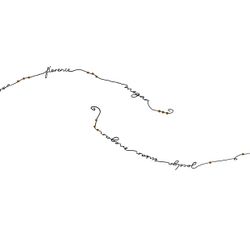

On the opposite wall to Pouakai, and also from the Aigantighe collection, are embroideries and paintings by the late artist Carol Anne Bauer (1935-2016). Bauer was born in New York City and studied painting, enamelling and textiles in the United States before emigrating to Aotearoa with her family in 1972. Bauer’s artworks intricately render in thread and acrylic paint microscopic minerals, fossils, sea anemones and other oceanic forms; the kinds of marine organisms whose skeletal fragments have come to form the limestone beds of the surrounding region.

Bauer settled in Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, and it wasn’t long before she was exhibiting with fibre arts groups—a field of artmaking that was experiencing a resurgence in Aotearoa throughout the 1970s. Bauer was interested in using unorthodox combinations of materials such as silk and nylon thread, dyes, perspex, velvet, metallic foils and light-reflecting powders; materials that offer different effects of light and texture. She was also interested in imbuing her works with mythological images and symbols, scientific imagery and ideas and thoughts based on her own readings of fantasy and psychology.

Bauer’s practice is not well known and little information about her is present amongst recorded and documented art history in Aotearoa—something many women artists have experienced, especially those working in ‘craft’. Juxtaposed here with Park’s ceramic sculptures, it is possible to see a connection between the two practices, where mark-making, organic motifs and a range of materials suggest alternative ways of thinking about the natural world, one which is insistently speculative.

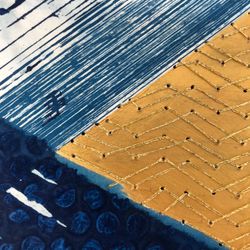

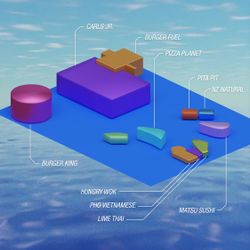

At the far end of the gallery, a large-scale film installation by Dilohana Lekamge. A Different Ocean (2021) screens alongside a new commission, A softer limestone (2023). Both works centre on Ram Setu, or Adam’s Bridge, a mysterious limestone shoal crossing the Palk Strait between Sri Lanka and India. Ram Setu is a unique geological feature and a site of foundational significance to these nations’ different religious groups. A Different Ocean recounts an episode within the Ramayana where Sita, the wife of Hindu deity Rama, is kidnapped by the demon king Ravana and later is shunned for having set foot in Lanka. This is told alongside the fall of Eve in Judeo-Christian religious narratives, using collaged footage taken during a family visit to Sri Lanka.

In A softer limestone the camera meditates over the striated formations of limestone scarps and cliffs around nearby Maungati and Kakahu. Lekamge narrates a number of different stories: the cosmic battle between a cyclone and a temple; her great aunt’s regular travels between India and Sri Lanka over Ram Setu on the Boat Mail Express (formerly the Indo-Ceylon Express); and opposing plans for the development and conservation of the Palk Strait, and the ecological and political futures at stake there. These events parallel environmental changes within Timaru’s landscape: the draining of wetlands to form pasture; the imposition of a coastal breakwater to encourage maritime trade; and the significant loss of mahinga kai which these changes have caused over the last two and a half centuries. Together, the two videos entwine remote pasts, mythologies and notions of deep time within the present landscape. In Lekamge’s videos, narrative cycles and recurring geological events, reflected in South Canterbury’s metamorphic terrain, become a means of excavating displacement and diasporic longing for a distant other.

Like water by water suggests multiple ways of understanding the complexity of geological, cultural and interior landscapes. The recurring patterns, processes and events found in each of the artworks become like deposits, carried by fast and slow moving currents that converge and withdraw. A singular understanding of history, place and time collapses. In their work, these artists pay attention to both minute and bird’s eye vantages, thinking through the landscape to reveal traces both expansive and granular, sudden and abiding.